Introduction 🌟

How do you boost the performance of your system? How do you pass a system design interview? The answer to both lies in mastering caching. Caches are one of the key components in system design, capable of making software run much faster at every level.

But when do you actually need a cache? What are eviction policies? How do you pick the right caching strategy?

By the end of this guide, you will know how to use caches effectively and avoid common mistakes.

What is a Cache?

A cache is a storage layer designed to keep frequently used data, reducing the need to fetch it from slower storage repeatedly.

Example: Browser Caching 🌐

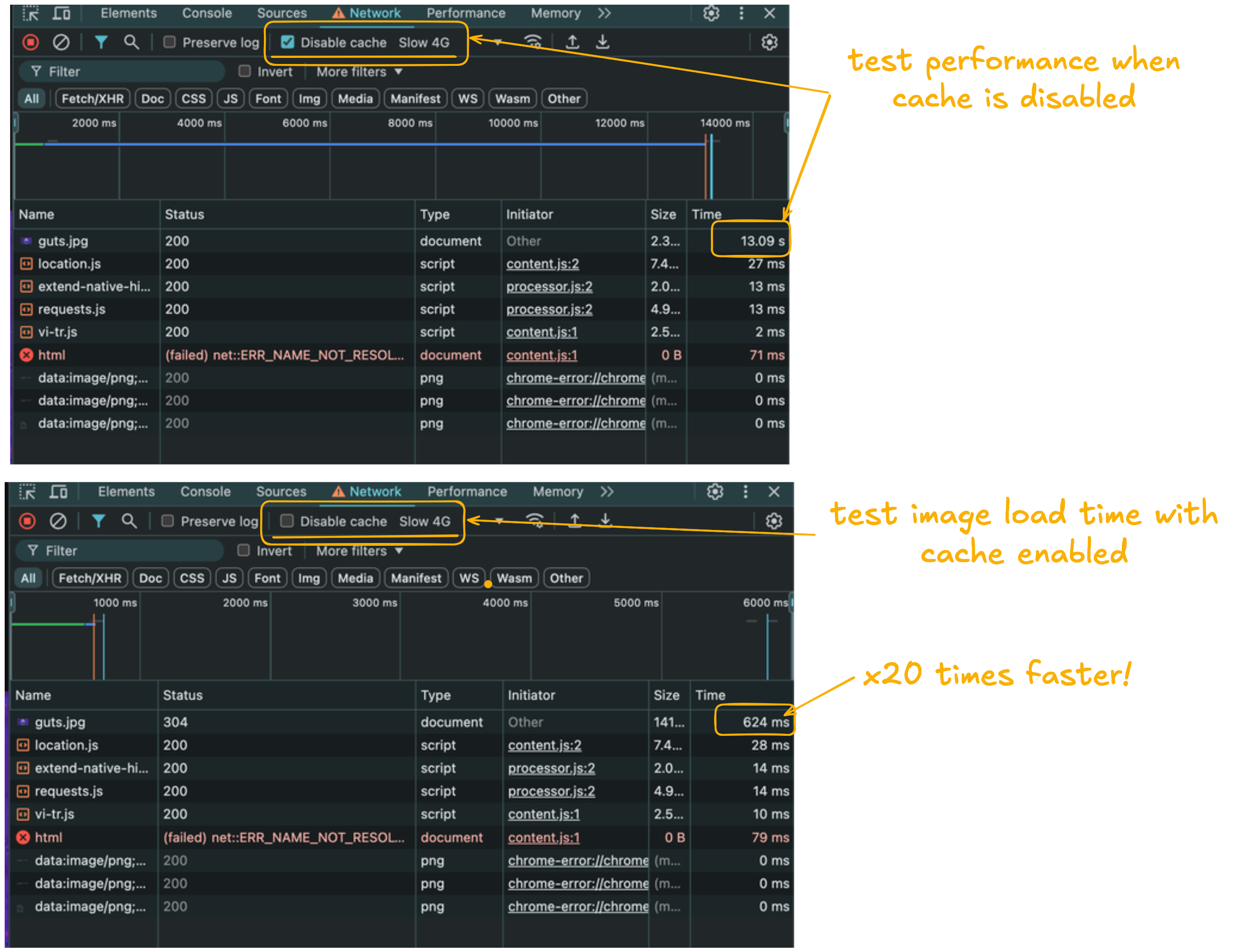

When you load a webpage for the first time, it may take some time, especially on a slow internet connection. However, subsequent visits are often much faster because the browser caches assets like images and scripts locally. This eliminates the need to download them again.

💡 The problem caching solves is performance.

Scenarios Where Caching Is Useful

- Complex Database Queries: Results from JOIN operations across multiple tables can be cached to avoid re-executing time-consuming queries.

- Post-Processing Tasks: Outputs from multi-step processes can be cached to avoid redundant calculations.

- Large Data Transfers: Frequently accessed network data can be cached closer to the client to reduce latency.

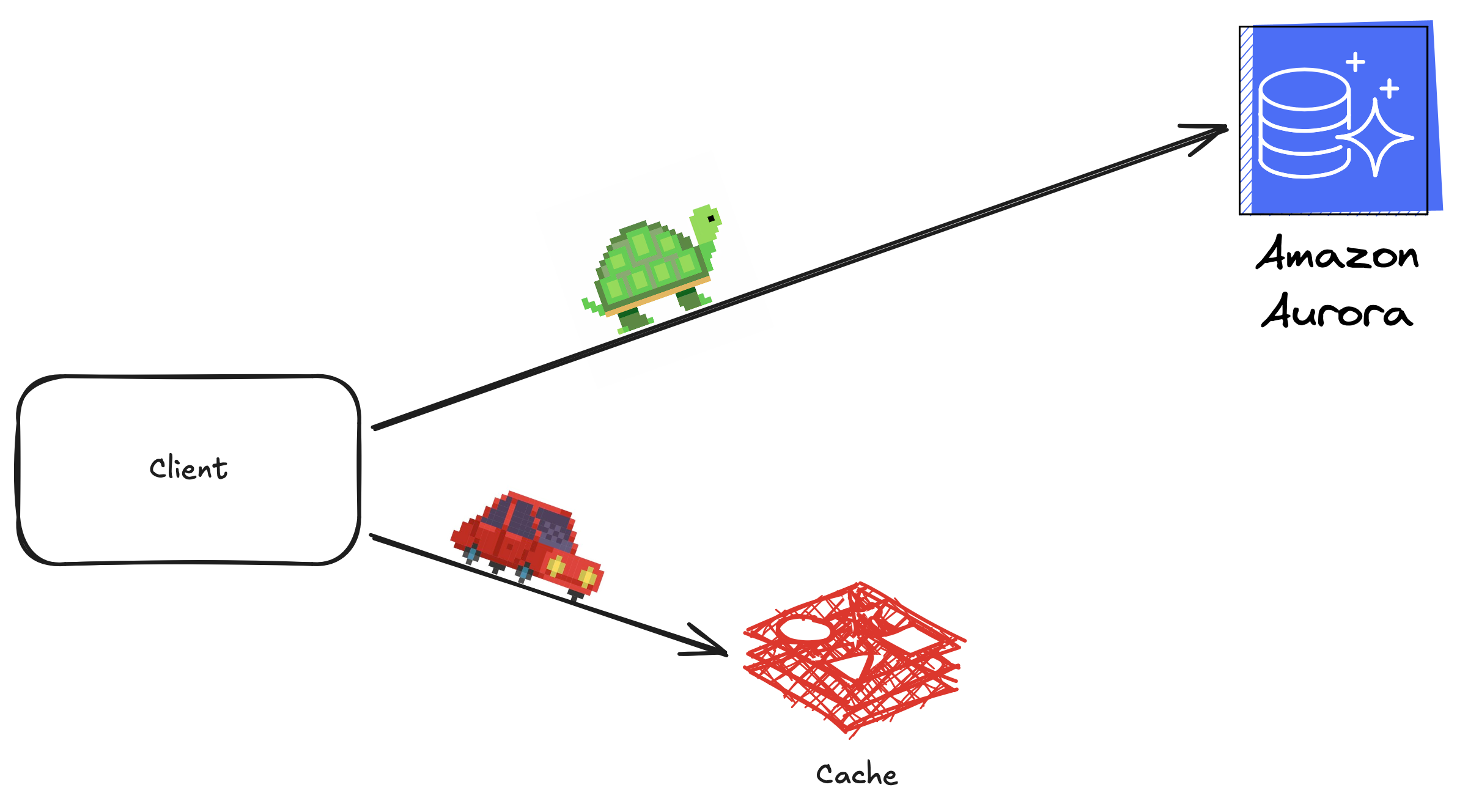

- Web Applications: A cache between the client and the database reduces load times by storing results of common queries.

The efficiency of a cache is measured by its hit ratio, the percentage of cache hits among all service requests.

When to Use (or Avoid) a Cache ⚖️

Caching is not always the answer. Consider these points:

When Not to Use Caching:

Your system has no performance issues. For example, if you run a simple blog with a few hundred visitors per day, the database queries are already quick. In such cases, adding caching introduces unnecessary complexity without significant benefits.

Your data changes constantly, making cache updates frequent and costly. Consider a stock trading platform where prices update every second. Using caching in this scenario would require constant invalidation and reloading, increasing overhead and risking data inconsistencies.

Your data is sensitive, like passwords or financial information, where caching could pose risks. For instance, caching account balances in a banking app might expose sensitive information or lead to inaccuracies that could violate strict data handling policies.

When to Use Caching:

- Systems with repetitive data access patterns.

- Applications where reducing latency or computational overhead is critical.

Types of Caches 🗂️

Hardware Caches 🖥️

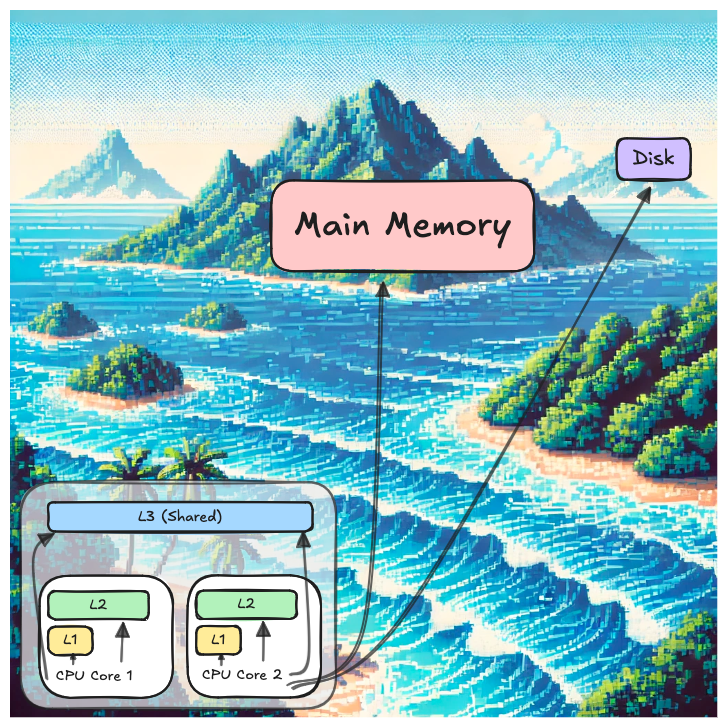

Hardware caches are built into the CPU and are extremely fast. They store frequently accessed data close to the processor:

Hardware caches are built into the CPU and are extremely fast. They store frequently accessed data close to the processor:

- L1 Cache: Smallest and fastest, located closest to the CPU core.

- L2 and L3 Caches: Larger but slower.

- Translation Lookaside Buffer (TLB): Maps virtual to physical memory addresses quickly.

Software Caches 📂

Page Cache 🧾

The operating system uses a page cache to store disk data in RAM. This reduces the need to repeatedly access slower storage.

Web Caching 🌎

Client-Side Caching: Web browsers cache assets like images and scripts. This is controlled by HTTP headers such as:

max-age: Specifies how long to cache data.no-store: Prevents caching, typically for sensitive data.

Shared Caching: Proxy servers and CDNs (Content Delivery Networks) serve multiple users by storing frequently accessed content closer to them.

- Proxy Servers: Reduce server load by caching popular data.

- CDNs: Improve response times by storing content geographically closer to users.

Application-Level Caches 🛠️

- Database Caching: Includes query results, indexes, and materialized views.

- Memoization: Caches the results of expensive function calls, useful in dynamic programming.

Deployment Models 🚀

Caches can be deployed as:

- In-Memory: Fast, as data resides in RAM. Examples include Memcached and Redis.

- Distributed: For scalability and fault tolerance, data is distributed across multiple nodes.

Cache Management 🛡️

Eviction Policies 🚪

When cache memory is full, items must be evicted. Common strategies include:

- Least Recently Used (LRU): Removes the least recently accessed item.

- First-In-First-Out (FIFO): Removes the oldest entry.

- Least Frequently Used (LFU): Removes the least accessed item.

Caching Strategies 🧩

Inline Caches 🛤️

- Read-Through: Cache retrieves data from storage on a miss and serves it to the client.

- Write-Through: Updates are written to both the cache and storage simultaneously.

- Write-Back: Updates are written to the cache first and later synced to storage, offering better write performance but weaker consistency.

Side Caches 🛠️

- Cache-Aside: The application explicitly manages cache reads and writes.

- Write-Around: Data is written directly to storage without updating the cache, suitable for rarely updated data.

Common Challenges 🛑

Thundering Herd Problem 🐘

Occurs when multiple clients overwhelm the system after a cache miss. Solutions include:

- Cache Warm-Up: Pre-load frequently accessed data.

- Soft and Hard TTL: Extend cache validity with soft TTL to avoid simultaneous cache expirations.

Cache Penetration 🚫

Happens when requests repeatedly query non-existent data. Solutions include negative caching to store “non-existent” responses temporarily.

Hot Key Problem 🔥

A single, heavily accessed cache entry can overwhelm a single node. Solutions include sharding the cache or using distributed caching.

Caching is a critical tool in system design that can significantly enhance performance when applied correctly. Understanding where, when, and how to use caching will help you optimize systems and ace system design interviews.